The Rwandan civil society is weak. That is everyone’s perception. At the launch of a UNDP’s civil society support fund, the Minister for Local Government, while acknowledging that civil society’s contribution is critical to the development agenda, regretted that it was too weak to optimally contribute. A recent EU civil society mapping report[1] elaborates on civil society’s weakness, describing it as too focussed on service delivery and less on policy advocacy. The international media, the regional civil society, even the chairperson of the Rwanda Civil Society Platform, all speak lowly of the Rwandan civil society. But what does that mean? And how has that played out thus far, in terms of defining Rwanda’s socio-political discourse on the one hand, and human rights advancement on the other.

This article aims to assess to what extend – or none thereof, civil society influences policymaking in Rwanda. It postulates that the ‘weakness’ of the civil society has pushed government bodies, informed on the one hand, by international best practices, and on the other by the ever-present quest for international recognition, to take up an ‘activist role’, filling a gap left by the ‘weak civil society’. To put things in perspective, the author focuses on the struggle to advance LGBTI rights in Rwanda, and how the Rwandan civil society is handling the post decriminalisation in practice.

How did we get here? To understand the civil society’s approach in advancing rights in Rwanda, one needs to look at the Rwandan culture, the legal and political framework, both underpinned by soft engagement and non-confrontational lobbying. From that standpoint, one sees that the Rwandan civil society has deliberately foregone its visibility and, to some extend, its legitimacy in the interest of silently advancing its agenda. It engages policy makers through ‘protected spaces’, created for that purpose by the polity. These spaces offer incidences for serene talks and behind the scene influence wavering. In this manner, civil society’s asks are either adopted or at least noted. Once a deal is quietly hammered down, the government goes ahead and takes credit for it. This is how the world is able to discover a country that upholds progressive policies.

Today, Rwanda is lauded for emancipating women, abolishing the death penalty, extending free healthcare and education to all. Rwanda became the sixth and latest African country to empower the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights to receive individual complaints against it, and the only one to extend a standing invitation to all UN/AU special mechanisms. Less known however, is the background advocacy work carried-out by the Rwandan civil to reach those developments.

Three years ago, the Rwandan government transcended regional prejudice and conservativeness to repeal article 217 of the draft penal code criminalising homosexuality, following a marathon advocacy campaign by local the civil society. But in a radio interview on the issue, the minister of justice was candid: ‘these NGOs do not know what they are talking about; the thought to criminalise homosexuality never crossed our mind!’ In all these happenings, Rwandan NGOs resisted calls from their international counterparts, to take full credit for their effort. They did not see the need to claim a spot at the podium; we got what we wanted, they said, let them enjoy their moment.

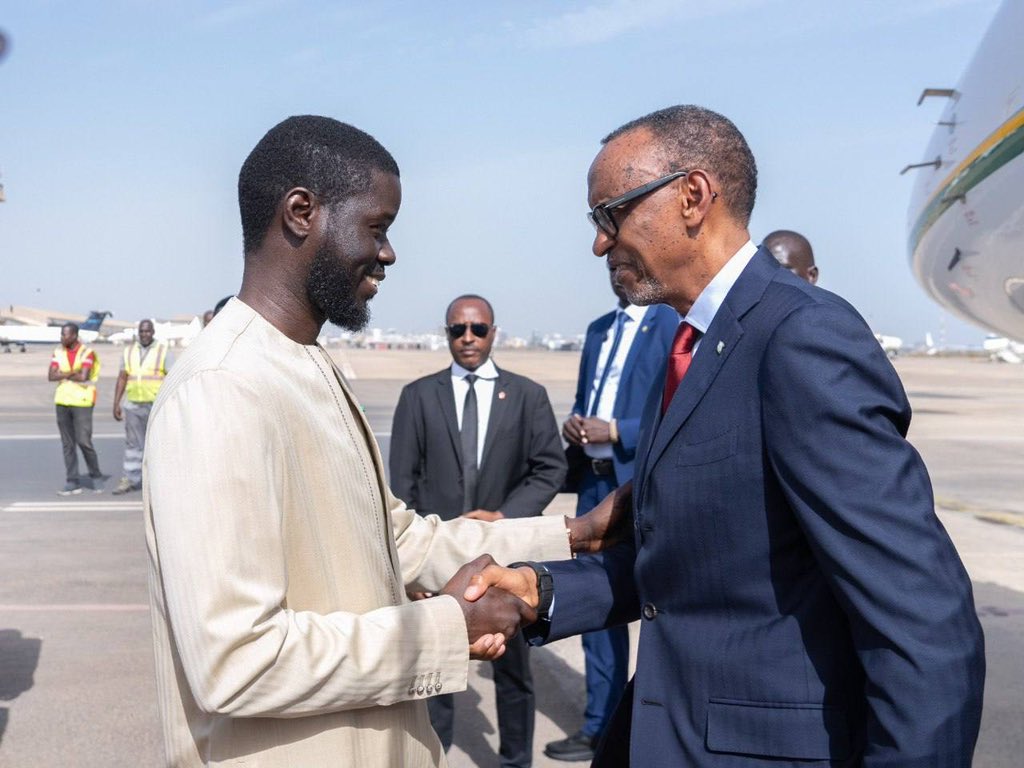

But the comments of the president on the Private Equity in Africa Summit, held in London in November 2009, succinctly captures the dynamics at play in Rwanda: ‘On the issue of homosexuals […] We have laws already in place that cater for existence and co-existence of different categories and create harmony in society and, I think it looks like we are headed to leaving like that rather than heightening tensions and bringing out unnecessary conflicts and debates that will not help the rebuilding of our country’[1][2].

In the past few weeks, there was mounting anxiety on the potential ripple effect, coming from the degrading status of LGBTI rights in Uganda and in the region. The decision by Kenyan Lawmakers to give up their plans to emulate their Ugandan counterparts and enact tougher laws against LGBTI, came as a relief.

The anxiety was based on two things: First, there is still no unanimity on the issue within the Rwandan civil society. Although the legal ship has sailed, many are those who have criticised pro-LGBTI activists and would like to have the debate reinitiated. Second, there is persistent stigma against LGBTI groups within the Rwandan public, especially fuelled by religious groups.

In any event, the Rwandan pro-LGBTI activists have not been idle; far from it. They have lately managed to secure groundbreaking policy milestones; for example, the National HIV strategy[2][3] has made costing for the import of lubricants, and earmarked ‘treatment as prevention’ for key populations. What this means is that HIV positive ‘Key populations’ (Men having Sex with Men and Sex Workers) will receive Anti-retroviral treatment regardless of their CD4 count; a service normally reserved for pregnant women; others being put on treatment only after their CD4 count has dropped below 200.

Better yet, the Strategy further pledges:

Support Peer education for Female Sex Workers (FSW) and Men having Sex with Men (MSM) also addresses the problem of gender-based violence to which they are particularly vulnerable;

Advocacy with law enforcement and local authorities to improve protection of FSW and MSM;

Strengthen FSW and MSM participation in policy development and program implementation;

Reduction of socio-economic vulnerability of sex workers by encouraging FSW to create associations and cooperatives.

Another interesting development is that while civil society advocacy did not result in the complete decriminalisation of Sex work, it led the government to remove jail term for sex workers from the penal code. Today, Article 204 of the penal code[3][4] dealing with sex workers reads:

Any person who engages in prostitution shall fulfil, for a period not exceeding one year, one or more of the following obligations:

1° not to leave territorial limits determined by the Court;

2° not to go to certain places determined by the court;

3° to be subjected to surveillance measures;

4° to seek medical treatment;

5° to periodically report to administrative services or authorities determined by the court.

Furthermore, while the campaign to have condoms placed in secondary schools was not successful, it led to the enactment of a policy to teach comprehensive sexuality education in secondary schools; a practice that was not only taboo before, but which was seen by the Rwandan society as profoundly immoral.

It is true that the partnership between government and NGOs strengthens government’s image and erodes NGO’s relevance. But that is fine, so long as it achieves the purpose, which is to secure the right.

Granted, a vibrant civil society opens up the wider society over time. Within a self-censured citizenry such as ours, many are those who are not aware of the existing spaces and opportunities to engage. A vocal civil society would send a message to the public that it is okay to disagree and voice one’s concerns, outside the ‘protected spaces’ – because it is indeed.

Also clear is the fact that we have our fare share of oxymoron within the Rwandan civil society. Zealous sycophants, keen to recycle government’s messages, for political accumulation, and the hope to be considered for the next reshuffle. These individuals pay lip service to a human rights based approach, and do, at times undermine advocacy campaigns. Any civil society advocacy that needs to be done, aught to start there; within the civil society itself.

All that said however, the sustainability of any change, lies in building government’s ownership around it. In my upcoming book, I explain why branded advocacy with obvious international inspiration and support has revealed ineffective. While international watchdogs have found it difficult to influence substantial policy shifts, less confrontational negotiations, especially locally driven, have registered remarkable successes. NGOs should invest in building in-country/local capacity to influence change from within rather than outside.

Investing in in-country legitimacy admittedly takes time and may be somewhat frustrating. However, it ultimately holds the key to advancing human rights, and is perhaps more efficient than riding on international endorsements that may not necessarily have in-country recognition. Regular appearances and active participation in technical fora, can indeed be crucial to earning respect and legitimacy, and thereby ability to influence. NGOs should increase their presence, ability to communicate their actions and network, especially using numerous platforms such as the sector working groups of the Economic Development and Poverty Reduction (EDPRS-II).

As a parting short, I would say that the Rwandan civil society is not that weak, as people might think. It is just that it operates within an environment where dialogue and consensus underpin any dispensation for engagement. An LGBTI-friendly normative framework is the floor, not the sealing. After that has been achieved, a lot still needs to be done to shape a Rwanda fit for all sexual orientations. These actions include, raising awareness among opinion leaders, decision makers and law enforcers (lawmakers, government, police, media, NGOs, churches, etc.). This does not necessarily require branding and publicity; Alas, the end will ultimately justify the means.

So, the civil society is weak? Granted. But where has it lacked? What has it failed to achieve? For those who wonder: Are they pushed, or do they jump? I see only one catchy answer – the latest in town: ‘les faits sont têtus’.

Posted 11th April 2014

[1] Organic Law N° 01/2012/OL du 02/05/2012 instituting the Penal Code

[2]Source: http://www.paulkagame.com/blog6.php

[3] Rwanda National Strategic Plan on HIV/AIDS 2013-2019

Leave a Reply