‘I feel like a lone cyclist riding on a ridge, I cannot stop pedaling lest I fall’ -Thomas Sankara

‘I feel like a lone cyclist riding on a ridge, I cannot stop pedaling lest I fall’ -Thomas Sankara

This week, on the sidelines of the mythical ‘Festival Panafricain du Cinema de Ouagadougou (FESPACO), a monument of Thomas Isidore Sankara was unveiled at the very place where he and other comrades were assassinated.

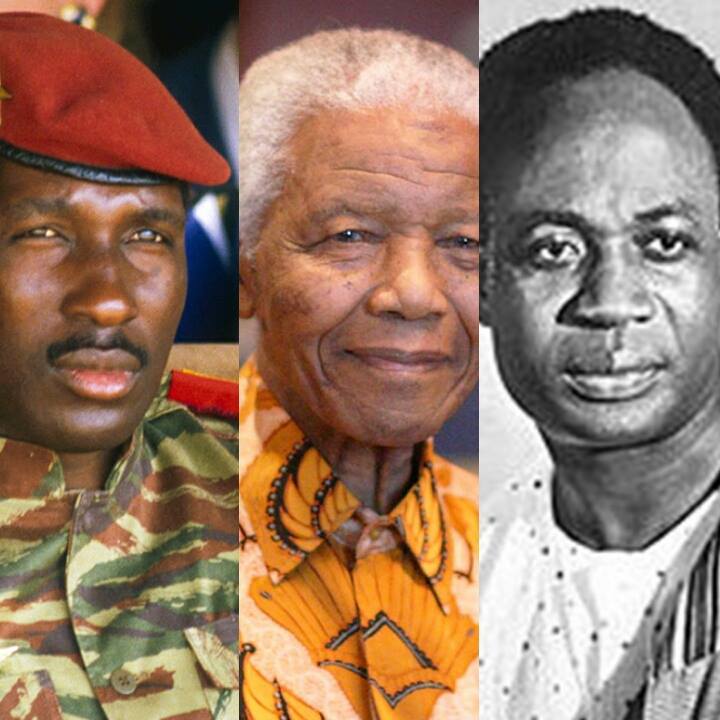

Africans are full of praise for the man as they are for Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba – ad posthumous – and all cry their untimely demise. Do not be fooled; those are crocodile tears, especially coming from Burkinabè, Congolese and Ghanaians. When the three men were alive Africans conspired with people of those three countries to oppose and ultimately betray them. I’m convinced that if they were alive today, we would betray them again. In fact, the three men are still alive; in your country, but Africans are trying all in their powers to betray them…

At the Funeral of late Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, Founding President of Ghana and Father of Africa’s independence, held in Conakry-Guinea in 1972, Cabo Verdean and Guinee-Bissau freedom fighter, Amilcar Cabral made a speech on Imperialism, betrayal and the African liberation struggle: ‘However, our tears should not drown the truth. We, as freedom fighters, are not weeping for the death of a man, for, as President Ahmed Sekou Touré often says: `What is man before the infinite and transcendent becoming of peoples and mankind? But we are weeping with hatred for those who were capable of betraying Nkrumah in the ignoble service of imperialism!’

When Sankara was alive, Burkinabè never willingly listened to him. He made them work hard to build Burkina-Faso while they wanted to stay idle and live off aid. Sankara coerced them into building their own railway line, while they wanted France’s ‘Bollore’ to do and manage it on their behalf; he encouraged them to wear garment made in Burkina-Faso, while they wanted western designer brands; he compelled them to respect women, while they wanted to be macho men. He forced them to be Burkinabès: ‘Upright men!’, while all they wanted was to remain ‘Voltaïque’; A French colony. When he was assassinated by Blaise Compaore, the whole country drew a sigh of relief; they are still paying the price for that sigh, to this day!

Of the elite he demanded discipline, probity and incorruptibility. He lived an austere life and forced them to do the same. He did not enrich his relatives; All the gifts he received, he deposited in the national treasury. The elite hated him, for he did not let them enjoy their glory. In practical terms, with Sankara’s death came the end of Burkina-Faso: The Land of Upright Men, and the return to Haute Volta – the French Colony.

Neighboring leaders saw in Sankara an indictment of their individual, family and political party’s excesses. While they sang Pan-Africanism louder than him, his deeds brought more dignity to the African people.

Neighboring leaders saw in Sankara an indictment of their individual, family and political party’s excesses. While they sang Pan-Africanism louder than him, his deeds brought more dignity to the African people.

– Cabral proceeds: ‘Treason to Ghana, as to the Congo and elsewhere in Africa, has a positive aspect: it shows the true human dimension of African man. And, in this specific case, it allows one better to grasp the true stature of Nkrumah as a political giant…’

In their ego-trip and greed, those who fought Sankara, Nkrumah and Lumumba found followers and supporters in and outside their respective countries…

Make no mistake, African martyrs sung by all today, were lonely yesterday, as Sankara explained, ‘I feel like a lone cyclist riding on a ridge, I cannot stop pedaling lest I fall’

It is no accident then, that the only friend Thomas had in that West African region was Jerry Rawlings, a man of similar vision, while his direct neighbor and elder, Houphouet Boigny, a self-proclaimed Pan-Africanist, was typically hostile to the younger comrade, undermining his projects, wooing his rivals and plotting the scheme to assassinate him.

During his presidency it wasn’t enticing to be an important person in Burkina-Faso because no glory would come of it. The Burkinabè elite and intelligentsia saw in Sankara a nuisance, a spoiler of fun. Burkinabè Trade-Unions opposed him, Civil Society marched against him and the international community undermined and mocked him!

Cabral further: ‘As far as his country’s development is concerned, we reject the slanderous criticisms by Africa’s enemies – and some of the Western press – even some cesspits which pass themselves off as being the African press-criticisms…’

One of the reasons I eschew, as much as I can, Embassy and NGO cocktails, it is because I meet that ‘petit bourgeoisie’ which killed Sankara there. Those who say to me, ‘aren’t Rwandans tired?’ aren’t performance targets putting pressure on them? Isn’t it pretentious of Rwanda to say it wants to phase out foreign aid?’; ‘Why did government ban French…’?

– What’s more pressure than poverty, ignorance and disease? Why should we care about French? I answer, although, it’s easy to dismiss foreigners, and much harder, African brethren, let alone Rwandans on this…

Sankara’s sin was to look for alternatives for his people, encouraging them to do it themselves and not wait for anyone else. By re-baptizing the country: Land of the Upright men, he wanted to instill dignity in his own people. However he faced resistance from entrenched networks, patronages of looting and neo-colonialism. His international infamy came from saying no to France; which used western media to disparage him, using slogans that are quiet familiar to us: ‘Democracy’, ‘Free Media’, etc.

Sankara’s sin was to look for alternatives for his people, encouraging them to do it themselves and not wait for anyone else. By re-baptizing the country: Land of the Upright men, he wanted to instill dignity in his own people. However he faced resistance from entrenched networks, patronages of looting and neo-colonialism. His international infamy came from saying no to France; which used western media to disparage him, using slogans that are quiet familiar to us: ‘Democracy’, ‘Free Media’, etc.

During Sankara’s time, neighboring leaders were primitive, heartless kleptocrates who looted their own countries and built schemes to racket their own citizens. They were able to do so with impunity, because France was protecting and maintaining them into power.

Sankara’s Burkina-Faso progress and self-worth were seen by France’s Mitterrand, Cote d’Ivoire’s Houmpuet and Senegal’ Senghor, as potentially bad influence to the West African region and our continent at large; as British Newspaper ‘the Economist’ could have titled it’s editorial then: ‘Many Africans see Sankara’s Burkina-faso as a model. They are wrong!’.

Sankara was loved by the youth in his neighboring countries and across Africa and loathed by the ‘Petit Bourgeoisie’ – as he called them. The youth would ask their leaders: ‘Why aren’t you doing as Thomas Sankara?’ Why are you good for nothing? So in his time, his success, but most importantly his ideas were seen as subversive.

As they came for him on October 15th 1987, freedom fighter Thomas Sankara quoted Revolutionary Che Guevara, as they came for him on October 9th 1967, who had quoted American Black Panther Megar Evers, as they had come for him on June 12th, 1963: ‘You can Kill a man, but you can’t kill an Idea.’

Far for being fatalist, this example infers the continuity of thought in the struggle for liberation.

Far for being fatalist, this example infers the continuity of thought in the struggle for liberation.

Alas! My name is Gatete-the-blogger, not John-the-Baptist; although to the Rwandan, East-African and African youth, I too may be the voice crying out in the wilderness, my aim with this story isn’t to point a finger to you and say: ‘Behold, there comes the messiah!’.

However I must preach to the African youth that Sankara, Nkrumah and Lumumba are alive today and more will come! But in their time; in our times, there too are mediocre presidents like Houmphouet and Mobutu; puppets like Senghor and Compaore. And as Apostle Matthew would advise in verse 7:16 ‘By their fruit you will recognize them’, and more importantly by the hostility of their neighboring presidents.

After identifying Thomas Sankara and Burkina-Faso in today’s Africa; After identifying Mobutu and Zaire, we must follow Comrade Amilcar Cabral’s advice in that timeless speech: “we must however draw the lesson from all events… to better understand the past, live the present and prepare for the future.

For example, what economic and political factors made the success of the betrayal of Ghana possible, despite Nkrumah’s personality, courage and positive action?

True, imperialism is cruel and unscrupulous, but we must not lay all the blame on its broad back. For, as the African people say: `Rice only cooks inside the pot. Nkrumah was killed by the cancer of betrayal, which we must tear out by the roots in Africa, if we really want to liquidate imperialist domination definitively on this continent…”

And to conclude with a message of hope: ‘But Nkrumah will rise again with each dawn in the heart and determination of freedom fighters, in the action of all true African patriots’; and rise again he did, personified in Thomas Sankara, but he was betrayed again, and he rose again personified in some of the African leaders of today.

We, the African youth must not listen to our mediocre leaders, who feel diminished by the deeds of Sankara(s) of today; nor must we listen to ‘the slanderous criticisms by Africa’s enemies – and some of the Western press – even some cesspits which pass themselves off as being the African press-criticisms…’

Africans must stop betraying their heroes today, then erect monuments to celebrate them as martyrs tomorrow!

There is a story also along these lines by Ken Sro-Wiwa; AFRICA KILLS HER SUN. Thanks for your wonderful article>