The Arab spring turned out to be an Arab nightmare, from which some like Tunisia are just waking-up; A warning, that sadly no African despot seemed to heed; a reality check for the African Union: jabbing an arrow at the heart of its structural loopholes and making a farce of its retrogressive policies.

The popular uprising in North Africa was unprecedented in many ways and taught us an important lesson: Africa has changed, for the better… Here is why:

1) Mobilizing approaches have changed: Educated, IT savvy youth, harnessing modern social media to organize and campaign, using old non-violent marches of the times of civil rights movements.

2) The masses have evolved: It used to be much easier to coerce or bribe the old guard, and indoctrinate hopeless illiterate young people. With increasing levels of education and access to information, it is difficult to insulate the youth.

4) Groundbreaking legal ramifications for the African Union:

The late OAU, acted as a club protecting status quo and ‘stayism’ among African presidents. The (OAU)AU convention on the prevention and combating of terrorism (2004) swept far broadly to preclude in Art. 1(3)(a)(iii) ‘General insurrection or any other mass civic action’ thereby undermining the whole right to picket and demonstrate;

This time however, the spring disregarded entirely ‘the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (2007)’. According to the Charter, no African president is to be toppled outside of an electoral process.

Art. 2(1) of the Charter maintains that its motives are to promote ‘Adherence [by African States] to the universal values and principles of democracy and respect for human rights’.

Its true agenda however, is captured in Art. 2(4): to ‘prohibit, reject and condemn’; repeated in 3(10): ‘condemnation and total rejection of unconstitutional changes of government’.

Indeed, no African convention directly recognises the right of the people for political participation. The right to freedom of assembly recognised by the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (Art 11) is clawed back by the observance of things such as national security, safety, ethics, etc.

All these conventions written by unrepentant Africa’s dictators were spectacularly overrun by the Arab youth.

The Arab spring read in the context of these treaties posed a significant legal dilemma to the AU executive council: The latter faced no choice but to recognise, albeit hesitantly, that what happened was a mere exercise of sovereign powers of the people; which is vaguely recognised in Art 6, as a passive right; requiring states to ‘ensure that citizens enjoy fundamental freedom and human rights.’

In the wake of the Arab spring, general consensus emerged that the youth in Egypt, Libya and Tunisia were actually not terrorists acting outside the ambit of democracy, despite what their leaders were saying.

This has now created an interesting malaise among the old club, at least those among them who have not been swept with the spring, and led to the ground shifting precedent, and realisation by all of us, that revolutions are legal and necessary, but most of all; inevitable!

On the short run, the impact of the Arab spring to sub-sahara is less visible. In an attempt to stimulate public uprising in Uganda, opposition leader Kizza Besigye launched the ‘work to walk campaign’, which was ruthlessly repressed by the state. This time however, the repression, conducted amidst the Arab spring, chocked the world opinion, but also the region, more than usual;

The call for ‘mass action’ launched by Kenyan opposition leader Mr. Raila Odinga, following a contested electoral process, degenerated into a catastrophic post-electoral violence, which costed lives of more than 1000 people.

After 27 years in power, Blaise Compaore was ousted in the same fashion as his Maghrebis counterparts, in a stunning two-day popular uprising.

Today, we are experiencing the unfolding of a popular and military coup against Pierre Nkurunziza, who had attempted to usurp his powers, and run for a third, illegal term [NDLR]

So, it is not that sub-saharan youth have not tried; it is just that there is something they may not be getting right just yet.

Be it how to face extremely violent state responses; or how to draw the attention of an African Union, which is more used to repressive government responses, than to mass revolutions.

On the long run however: there are numerous lessons learned here:

The people, especially the youth – which constitute te majority of the people of Africa – have realised that they do actually detain the power – and that, both in the north and in the south of the Sahara;

The penetration of information technology (mobile phones, internet), the use of social media (facebook, twitter), have shifted the paradigm. They are effective tools for political influence and mass campaigning, and will play an increasingly critical role, going forward.

People will not eat democracy, but they would like to have a say on what they eat. Power based on the old dichotomy of prioritising development over freedoms on the one hand, or offering freedoms in misery on the other, is rather precarious. Sooner or later the yearning for both is inevitable. People do not have to choose.

Once again, education is the best civic/political empowerment that can be given to the people; and its increase on the African continent presages good democratic days to come;

But the question remains: How much civic awareness and maturity is there? Why did the people of Egypt briefly replace Mubarak with Morsi, only to find out that they had jumped from a frying pan into fire (Read: from dictatorship into Islamism) and quickly organise for a ‘recall?’

A colleague from Ethiopia asked me to make previsions on How can the revolution trickle down past the Sahara. My answer was that for some, the Revolution is here. For others it might come in the form of soft change, in a short run, with much more impact in the long run. With the latest events in Senegal, Burkina-Faso and now Burundi: I am humbled!

Hopefully this will have given African politicians some food for thoughts. The good ones will see the inevitability for change and start preparing for their succession. The bad ones will brass for harsher measures to nip the protests in the bud before they take ground.

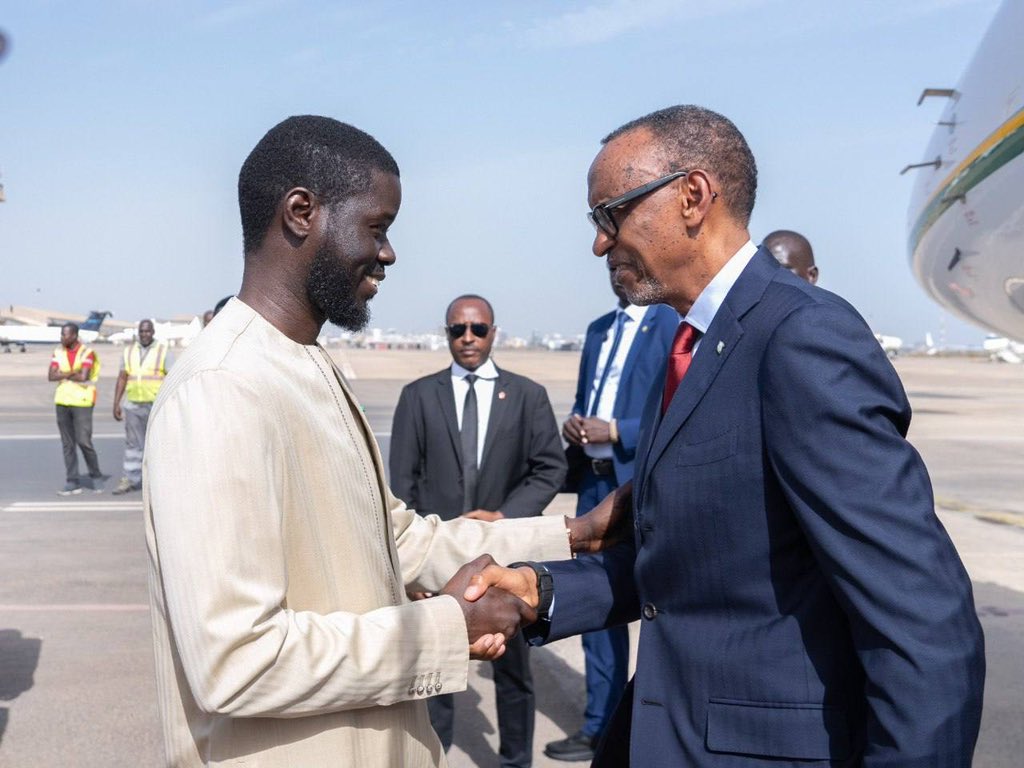

Have we all learned this time? Let’s wait and see. While we wait, I think it’s safe to say that the current president in Egypt, Al Sisi, in Senegal Macky Sall and the next one in Burkina, understand that they are trading on thin ice, just like dictators are having sleepless nights, while we, the African youth, are readier than ever, I hope…

Posted 1st November 2014

Leave a Reply